Part XV of Amulets & Talismans

The mythical half-human creatures known as Selkies can be found in Norse, Scottish, Irish, Icelandic, and Faroese stories. Selkies shapeshifted between human and seal form by shedding and replacing their skins.

The word “Selkie” comes from the Scottish word selch, which means “grey seal.”

The most common form of Selkie story involves a human man — usually a fisherman — stealing and hiding a Selkie’s skin so that she is trapped in the form of a beautiful woman and has to become his wife instead of returning to the ocean. In the story, the hidden sealskin is found years later — often by the children the Selkie had had with the man — and the Selkie woman remembers herself, takes her skin back, and returns home to the waves, never coming back on land again (though in some children’s stories, she can visit her family on land once a year.)

There were also male selkies who were said to have seductive powers over human women, usually women in unhappy marriages or who were waiting for their seafaring husbands to return to them. In one story from Orkney, such a woman would make contact with her Selkie by shedding seven tears into the sea.

Selkies are often described as attractive, graceful, kindly, and amorous. Humans were said to fall hopelessly in love with them, in the same way that men were said to do with mermaids.

Most of the communities that Selkie tales originate from are near the sea or rely on the sea for their livelihoods, e.g. the Chinook people on the West Coast of America have a story of a boy who changes into a seal.

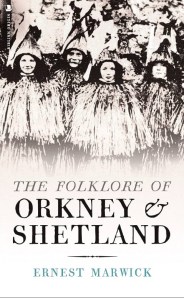

The children born of a Selkie and a human often had syndactyly (webbed fingers and / or toes) showing their half-Selkie parentage, though in The Folklore of Orkney and Shetland by Ernest Marwick there is a story of a woman having a son with a seal’s face after falling in love with a Selkie man. Marwick also mentioned a group of Selkie descendants with greenish-white skin that cracked in various places.

Tales involving seals are also prominent in Inuit folklore.

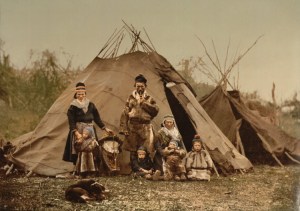

The Sami people once existed in areas of Scandinavia. They divided into two groups — mountain Sami and sea Sami. Mountain Sami are known for herding reindeer but sea Sami were fishermen and travelled in kayaks made out of sealskins, as the Inuits did.

The sea Sami of Scandinavia had so much skill and precision in a boat and the best knowledge of the ocean and coastline. It was said that their children could capsize their kayaks then turn their boats right-side up again — with only their hands and a flick of the hips — by age five.

The sea Sami kayakers wore sealskin clothing to protect themselves from getting waterlogged. On long journeys, they stitched themselves into their kayaks for better protection against storms and huge waves.

Their sealskin kayaks would remain light until they became saturated. Once this happened, the kayaks would settle deeper — sometimes just under the sea’s surface. Then the kayakers would have to come ashore, remove their sealskins and dry off in the sun before resuming their travels. Perhaps passersby saw this happening and invented the legend of the Selkies to make sense of what they were seeing.

In Scottish oral tradition, seals were also either thought to be the souls of the damned, people who had been bewitched, or the reincarnated forms of humans who had died at sea.

As this article from Dig It Scotland says, seal flipper bones look rather similar to human hand bones, so people who had seen seal bones in the past could be forgiven for imagining that one could wear the skin of the other!

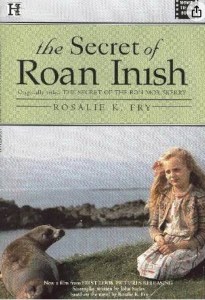

Selkies inspired the novel The Secret of the Ron Mor Skerry by Rosalie Fry, which was adapted into the recent film The Secret of Roan Inish (something that this author would very much like to watch).

You can find the tale of an Irish Selkie on this page.

The Conneely clan of Connemara was said to be descended from seals, which meant that members of that clan couldn’t kill a seal as it would bring them bad luck. Eventually Conneely was changed to Connelly.

Some stories about the Selkies claimed they could only assume human form once every seven years, or when the tide was just right (often the time of springtide). They were believed to change into humans only once in seven years because they were condemned souls or even fallen angels.

Belief in the Selkies made it so there was a superstition in Scotland that killing a seal would bring bad luck.

Some tales in Shetland claimed that Selkies lured humans into the sea during midsummer, and those humans were never seen again. According to some of these tales, their seal-form was only used for travelling through the sea from their homeland, where they assumed human guise and breathed air once more. Each sealskin was special and irreplaceable.

In the story “Gioga’s Son” a group of seals (really Selkies) were resting in the Ve Skerries and a group of Papa Stour fishermen ambushed them, then skinned them. The blood spilled made the seawater suddenly rise, and one fisherman was left stranded. The Selkies recovered in their human forms but grieved over the loss of their sealskins, without which they could never return home. A Selkie woman named Gioga made a bargain with the fisherman, carrying him back to Papa Stour in exchange for the return of their skins.

In Faroese folktales, the Selkie woman has a Selkie husband and Selkie sons whom she returns to after rediscovering her hidden skin — but then the human fisherman who had forced her to marry him kills her Selkie family, so she lays a curse on the human islanders, saying that some will drown and others will topple off cliffs and slopes until so many men have been lost, they will be able to link arms around the island of Kalsoy. Deaths on the island are sometimes attributed to this curse.

On the other hand, in another Selkie tale, the fisherman husband goes to sea in spite of his Selkie wife sensing an impending storm and warning him not to go. She dons her sealskin to save him from drowning, but this prevents her from ever returning to him as a human woman again.

The Selki mentioned in “A Dark Heritage” are not attractive or kindly at all. They have bony whiskers similar to catfish, are elusive (perhaps endangered) and won’t think twice about eating any human that strays into their territory.

Sealskin and Lightning

According to ancient Roman Pliny the Elder’s Natural History, seals (or “sea-calfs”) were one of the animals which were never struck by lightning.

This led the Emperor Octavius (or Augustus) to always carry a sealskin around with him, as he was afraid of being hit by lightning ever since a slave (who was bearing his litter) died from a lightning-strike.

The special tent Moses used to enter to converse with God in the Bible’s book of Exodus had a covering of sealskin. God took on the form of a pillar of clouds here (almost like… a storm) to conduct these meetings.

Interesting stuff about lightning in ancient times can be found here

Gigantic lightning-creatures known as Brontides stride across the world in the Nighthunter series.

Other parts of Amulets & Talismans:

15 thoughts on “Selkies and How to Protect Yourself Against Lightning”